Frank Jones

114591

August 5 - September 13, 2020

179 E Broadway, New York, NY 10002

Everything we see in life creates and informs our “reality”, and we take it for granted that what we’re seeing aligns with other humans’ perception. But for some visionary individuals, their perceived world is something wildly more complex and strangely populated.

Frank Jones (1900–1969) descended from a long line of Southern slaves who resettled in Clarksville, TX to make a living picking cotton. He was born with a “caul” (part of the fetal membrane) covering one of his eyes, and in African American folklore a “veil” at birth signaled the child would possess the ability to see into the spirit world. Jones claimed to have access to this supernatural realm as early as the age of nine, and he routinely described seeing “haints” (or haunts), similar to spirits, devils and ghosts. These haints were both male and female, of many nationalities, and to him, completely real and universal.

Following a traumatic childhood– both of his parents abandoned him before the age of 6, Jones repeatedly fell into trouble and spent the majority of his adult life in and out of prison, possibly for crimes he never committed. Many people who knew Jones’ story, including a Texas state senator and multiple prison guards at the Huntsville State Prison in Texas where Jones was incarcerated, believed he had been wrongly accused. It was also widely speculated that he had a severe learning disability and suffered from a mental illness, which would have left him as an easy target to take the fall for someone else’s crimes, particularly in such a segregated and racist climate as Clarksville in the mid-20th century.

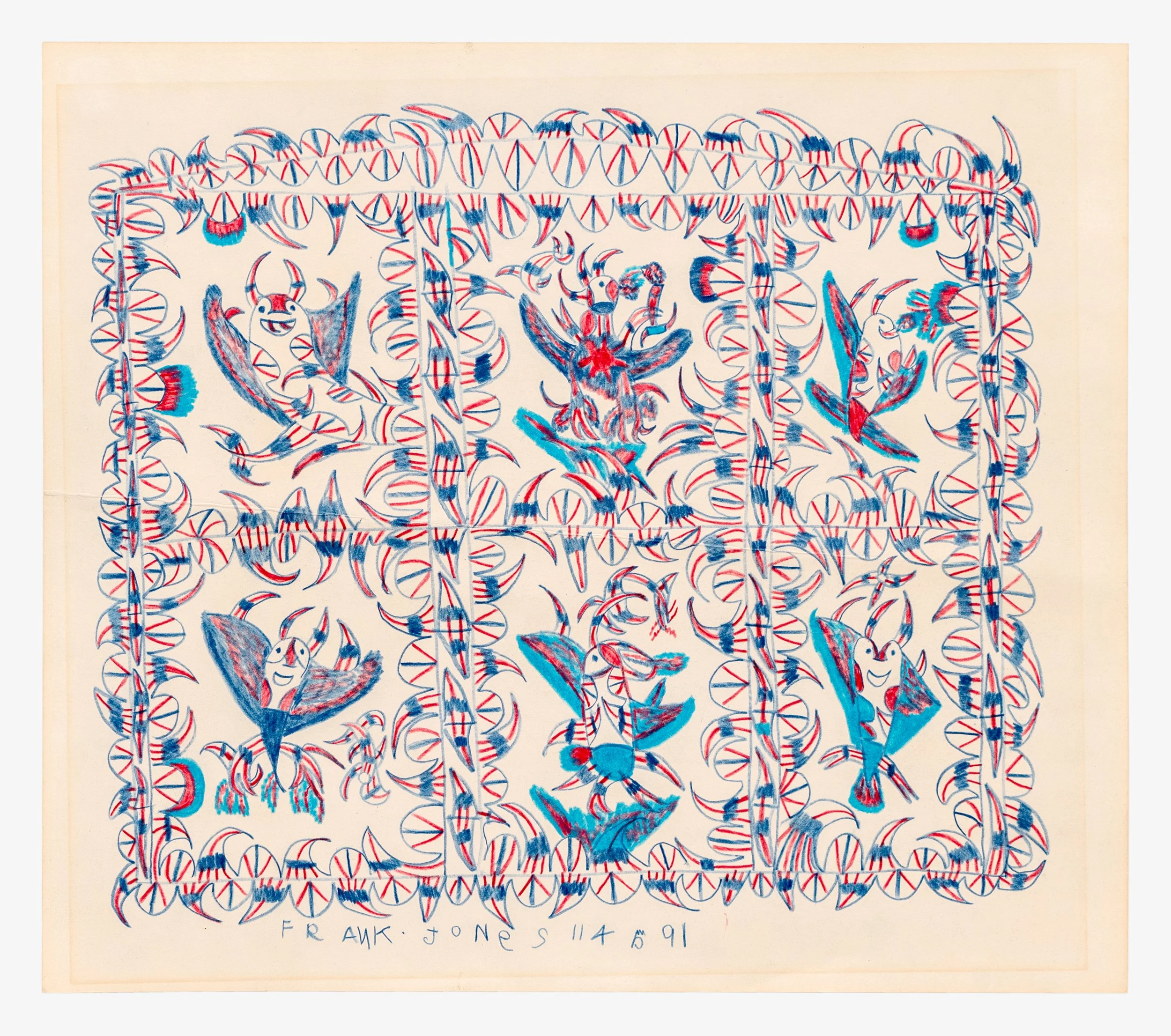

Around 1960, while serving a life sentence for murder, Frank Jones began obsessively creating what he called “devil houses,” drawings that documented the grinning, horned and lightning-spewing creatures he had been tormented by since his youth. During an interview, he once explained that these haints smiled to lure you into trouble, begging “you to come closer to drag you down.” By the time of his death, Jones had created roughly 500 drawings using stubs of red and blue pencils salvaged out of trash cans that had been discarded by the prison’s accountants. Despite eventually being offered a larger variety of colored pencils, red and blue remained Jones’ preferred color scheme and symbolized fire and smoke in his eyes. When asked about his work, he explained that the spirits he rendered on paper were exactly as he had seen them in life. These spirits, such as elongated flying-fish figures and winged-devils, were often confined to small rooms, much like his own prison cell, perhaps in an attempt to neutralize their power and cease their torment of him.

Clocks also became a repeated motif in Jones work despite his not being able to tell the time. They are found in almost half of his drawings, usually with multiple hands and wildly-spinning appendages, and reference two real-world clocks– one a clocktower near his home that had terrified Jones as a young man and was believed to be haunted, and the other a prominent clock in the courtyard of the Huntsville State Prison, where Frank Jones spent much of his time working on his drawings. There is an obvious link to the concept of “doing time” as a prisoner, but the clocks also directly link Jones’ works to his physical location in prison, where he believed devils and manipulative spirits surrounded him. In this light, these drawings can be seen as a documentary effort to give us a glimpse into the artist’s inner world, and they became Jones’ most intentional means of relaying his otherworldly visions to the outside world.

Like many poor Black children in the early part of the 20th century, Jones never attended school or learned to read and write. At first, he simply signed his drawings with his prison number– 114591, but eventually someone showed him how to write his name, which he then began adding to the bottom of his drawings. As an artist, Jones’ work might never have seen the light of day had a prison guard not jokingly entered one of his works into a prison art contest in 1964 highlighting prisoners’ arts and crafts. Murray Smither, who worked at an art gallery in Dallas, was in attendance at this show and was immediately struck by the power of Jones’ work, which won the contest. Smither quickly worked with his boss, Chapman Kelley, to organize Jones’ first-ever gallery exhibition at Atelier Chapman Kelley Gallery in Dallas.

The show was a success, and Kelley and Smither were soon able to provide Jones with larger sheets of paper to work on and money from the sale of his drawings, which Jones used to purchase small prison luxuries such as a radio and wristwatch. Being a recognized artist also provided Jones notoriety among his fellow prisoners in Huntsville and lead to a series of press interviews. Following a push to free Jones by those who believed in his innocence, he was finally granted parole in February,1969; however, before being able to enjoy his freedom he was brought into the prison hospital and quickly died from progressive liver disease. In his will, Jones left behind instructions to establish a small fund to provide scholarships to high school art students in his hometown of Clarksville, showing that he still had good will towards humanity despite the whirlwind of challenges in his life.