Inventing Abstraction

Nonrepresentational Self-Taught Art

February 13 - March 21, 2026

-

Emery Blagdon (1907 – 1986) spent years filling a barn on his rural Nebraska property with delicate hanging mobiles, sculptures, and paintings. Using wire, found objects, sheet metal, and elemental compounds sourced from a local pharmacy, Blagdon believed his creations generated electromagnetic energy with immense healing properties. He considered his works and overarching project a “healing machine” and did not regard his assemblages as art.

-

Hawkins Bolden (1914 – 2005) was permanently blinded at the age of seven, following a series of accidents. In his later years, Bolden dedicated himself to maintaining a vegetable garden in the backyard of his family home. At the urging of a relative, Bolden began creating scarecrows to protect his garden and its highly valued produce. This pursuit became his passion in life, and he carefully constructed hundreds of scarecrow assemblages entirely by touch, using found materials sourced from his alleyway and from around his neighborhood.

-

On the eve of the Great Depression, Thornton Dial (1928 – 2016) was born into a sharecropping family in rural Alabama. During his life, Dial directly experienced the trauma and tumultuous times of the Jim Crow laws and the civil rights movement. Inspired by individuals like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Dial created art to address and confront the blatant issues of racial oppression and inequity in the United States. His works are a powerful commentary on the world he lived in, and his visual style ranges from narrative storytelling to more allegorical works that use abstraction to poetically express his political and personal beliefs.

-

Minnie Evans (1892 – 1987) was a self-taught Black artist born to rural farmers in North Carolina. As an adult, she worked as a gatekeeper at a public garden, which may explain the striking floral motifs displayed in many of her artworks. Evans claimed that she primarily found inspiration from dreams, and her fervent belief in God also played a central role in her artistic practice. In her own words, “This art that I have put out has come from the nations, I suppose, that might have been destroyed before the flood.… No one knows anything about them, but God has given it to me to bring back into the world.” Evans’s drawings tap into surrealism unconsciously, and they feel free of self-consciousness and self-doubt, as they were made solely for her own enjoyment and use. “Something told me to draw or die,” Evans once stated.

-

Madge Gill (1882 - 1961) was a self-taught British artist and self-professed psychic medium and healer. She fervently believed that a spirit guide named “Myrninerest” guided her hand and authored her drawings, which feature recurring pale-faced figures and apparitions, swirling geometric patterns, architecture, and cryptic writing. Gill’s work is included in the collections of Centre Pompidou, Paris, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne, and Whitworth Museum, Manchester. Exhibitions include Parallel Visions at LACMA, Los Angeles (1992), Outsiders at Hayward Gallery, London (1979), Floral Fantasies at the Wilhelm Hack Museum (2019), and Brutal Beauty at Barbican, London (2021). Gill’s largest known work was recently on display in Foreigners Everywhere at the 60th Venice Biennale (2024), curated by Adriano Pedrosa.

-

Nnena Kalu (b. 1966), who recently won Britain’s 2025 Turner prize, creates two-dimensional works on paper, sculptures, and complex installations. Through binding, layering, and wrapping materials, she explores space, scale, and materiality. Kalu’s installations often begin with multiple compact cocoons, or boulders, of textiles and paper, tightly packed in cellophane and sealed with tape. The artist’s energetic installations and drawings become an extension and record of her physical movements and focus on the relationship between her body and the abstract forms she chooses to depict.

-

Susan Te Kahurangi King (b. 1951, Te Aroha, NZ) doesn’t speak with words, but she is able to share her unique worldview and personality through an extraordinary drawing practice that began at a very early age. While King stopped speaking around age four, she was a prolific artist from then on through her thirties, when she suddenly stopped making art. In 2008, almost twenty years later, she resumed her work, picking up right where she left off. Since then, King has continued her remarkable journey with a steady output of drawings in graphite, pencil, crayon, ink, and various pens. Her references are whimsical, wide-ranging, and sometimes haunting, and her drawings blur the lines between representation and abstraction.

-

For years, Joseph Lambert (b. 1950) took a bus to work daily in a protected atelier, where he focused primarily on woodworking, making colorful furniture of joined lengths of plank, paneling, and lathes by fitting the pieces together like puzzles. This experience appears to inform his prolific drawing practice. Although Lambert does not speak readily, he starts each drawing with language and continues to write over these letters until they completely disappear under a mass of marks. He lays his words down in stratum-like geological layers until they are abstracted into superimposed lines of color. Visually, the artist’s abstract compositions can be perceived as vast foggy landscapes that lead into magical forests or the edge of the sea.

-

Using his own particular kind of formalism, Michael Angelo Mangino (b. 2004) creates work independently from the history of abstraction in art, while, at the same time, adding a new contribution to it. Mangino does not generally speak or write to communicate with the outside world, but he is uncannily able to paint with complete fluency and without hesitation, resulting in paintings that represent a complex and private non-objective language.

-

Marlon Mullen (b. 1963) is widely known for his kaleidoscopic paintings, which feature interlocking shapes of color and tactile paint and reference images found in art magazines from the library at NIAD Art Center, where he has worked since 1986. An intuitive formalist, Mullen paints precise shapes in bold swirls of vivid colors, creating topographical pools of paint and confident graphic lines that delineate forms that had formerly served to make an image. As he distills and reconstructs his references, the paintings come to withhold what one might consider vital information, prioritizing previously minor or overlooked details. Mullen has created his own idiosyncratic pictorial universe that toggles between representation and abstraction.

-

J.B. Murray (1908 - 1988) was a farmer and sharecropper who lived in rural Glascock County, Georgia. At around the age of 70, Murray began experiencing hallucinatory visions and communications that he believed were directly from God. During a visionary trance, he described the sun descending from the sky and landing in his yard while he was watering his vegetable garden. "After that," he told the artist, Judith McWillie, "The eagle crossed my eye... a spiritual eagle. You know the eagle can see farther than any other bird in the world, and that's why I can see things some folks can't." Murray considers his drawings and paintings to be direct transcriptions of the word of God, which he translated while living, by reading through vials of water from his property’s well.

-

Melvin Edward Nelson (1908 - 1992) lived and worked as a recluse on his seventy-acre farm in Colton, Oregon. The artist developed a highly idiosyncratic form of scientific research, which he conveyed through abstract paintings and drawings made with watercolors and handmade pigments derived from soil samples taken from his property of UFO landing sites. In his mind, these traces of extraterrestrial intervention and supernatural occurrences are embedded in his works, which are all signed as M.E.N. (“Mighty Eternal Nation”). On each drawing, Nelson inscribed the date and time it was made, recording for himself and the world his cosmic ideology.

-

Born in Jalisco, Mexico, Ramírez (1895–1963) is widely considered to be one of the 20th century’s self-taught masters of drawing. Ramírez produced approximately 450 known drawings and collages during his 15-year stay as a psychiatric inmate at DeWitt State Hospital in Auburn, California. Through myriad sophisticated and recurring pictorial strategies, his singular artworks constitute a stirring testament to themes of poverty, alienation, immigration, confinement, and memory. Ramírez, who was diagnosed with catatonic schizophrenia, moved through a series of psychiatric institutions until 1948, when he was sent to DeWitt, where he remained until his death in 1963. While at DeWitt, Ramírez turned to drawing as a primary means of expression, using whatever materials were at hand, including discarded scraps of paper that he often collaged together with a crude impasto made of mashed potatoes and his saliva.

-

Judith Scott (1943-2005) was born in Columbus, Ohio, along with her twin sister, Joyce. In childhood, when it was recognized that Judith had Down syndrome, she was placed into an institutional asylum, where she became completely isolated from the world around her and her family. Eventually, it was recognized that Judith Scott was deaf, as well. After a meditation retreat as an adult, her sister Joyce realized that she needed to find Judith, which she did. Soon after, at around age forty-three, Judith joined Creative Growth in 1987 with the help of her sister. Fabric and items stolen from the art studio quickly became her passion and medium of choice, and for the next eighteen years of her life, Scott created sculptures using yarn, twine, and strips of fabric to wrap and knot around an array of mundane objects such as keys, plastic tubing, bicycle wheels, and a shopping cart.

-

Abraham Lincoln Walker (1921 - 1993) moved to East St. Louis, Illinois at the age of seven. A house painter by trade, he worked to understand basic palette and composition techniques. As an artist, Walker leaned toward representational depictions of his neighborhood, and many of his canvases still burst with odes to Black culture, featuring bright colors and brushstrokes that feel in line with jazz syncopation and rhythm. Much of Walker’s work from the late 1960s through the early 1970s features elongated, masked figures displaying ambiguous relationships and gestures, while set in desolate landscapes. Over time, the artist’s figures became more fragmented and distorted, with a visionary, celestial flair, and faces, limbs, and other barely identifiable human forms becoming entangled in time and space, yet still fully capable of communicating their psychic transcendence and wisdom.

-

Sculptures attributed to “The Philadelphia Wireman” were found abandoned in an alley off Philadelphia’s South Street on trash night in the late 1970s. Their discovery occurred in a neighborhood that was rapidly changing and undergoing extensive renovation at the time, and no attempts to locate or identify the artist were successful, suggesting the works may have been discarded after the maker’s death. The entire collection totals approximately 1200 sculptures, along with a few small drawings made on found paper with markers. The dense construction of these assemblages feels singular and obsessive, and the works generally display a wire armature (or exoskeleton) that firmly binds a bricolage of found objects, together including plastic, glass, food packaging, umbrella parts, tape, rubber, batteries, pens, leather, reflectors, nuts and bolts, nails, foil, coins, toys, watches, eyeglasses, tools, and jewelry.

Curated by Jay Gorney

Abstract art made by self-taught artists is the result of sheer invention. Unlike the canonical artists of the early twentieth century, who explored abstraction as an expression of rebellion against traditional modes of representation, self-taught artists often work without any awareness of art history or what came before them. In this sense, there is nothing to mimic, adulate, or reject; abstraction emerges as a primary visual language.

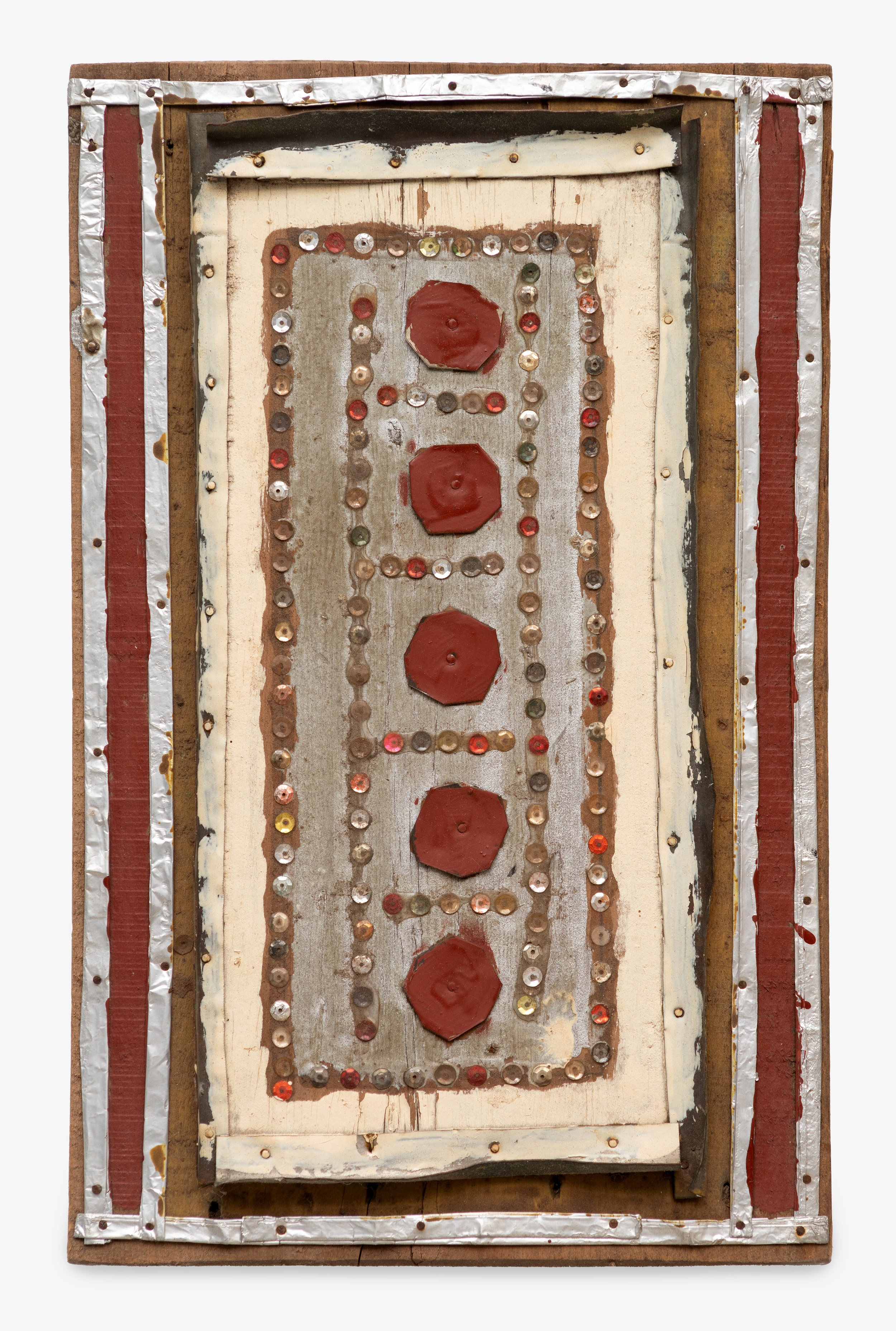

The sheer range of nonrepresentational practices by these artists is compelling. Limited access to traditional art supplies leads some towards the use of found materials and unconventional supports. In their hands, tree branches, old stop signs, worn clothing, and bones are stripped of their original meaning and reconfigured into highly personal abstract cosmologies.

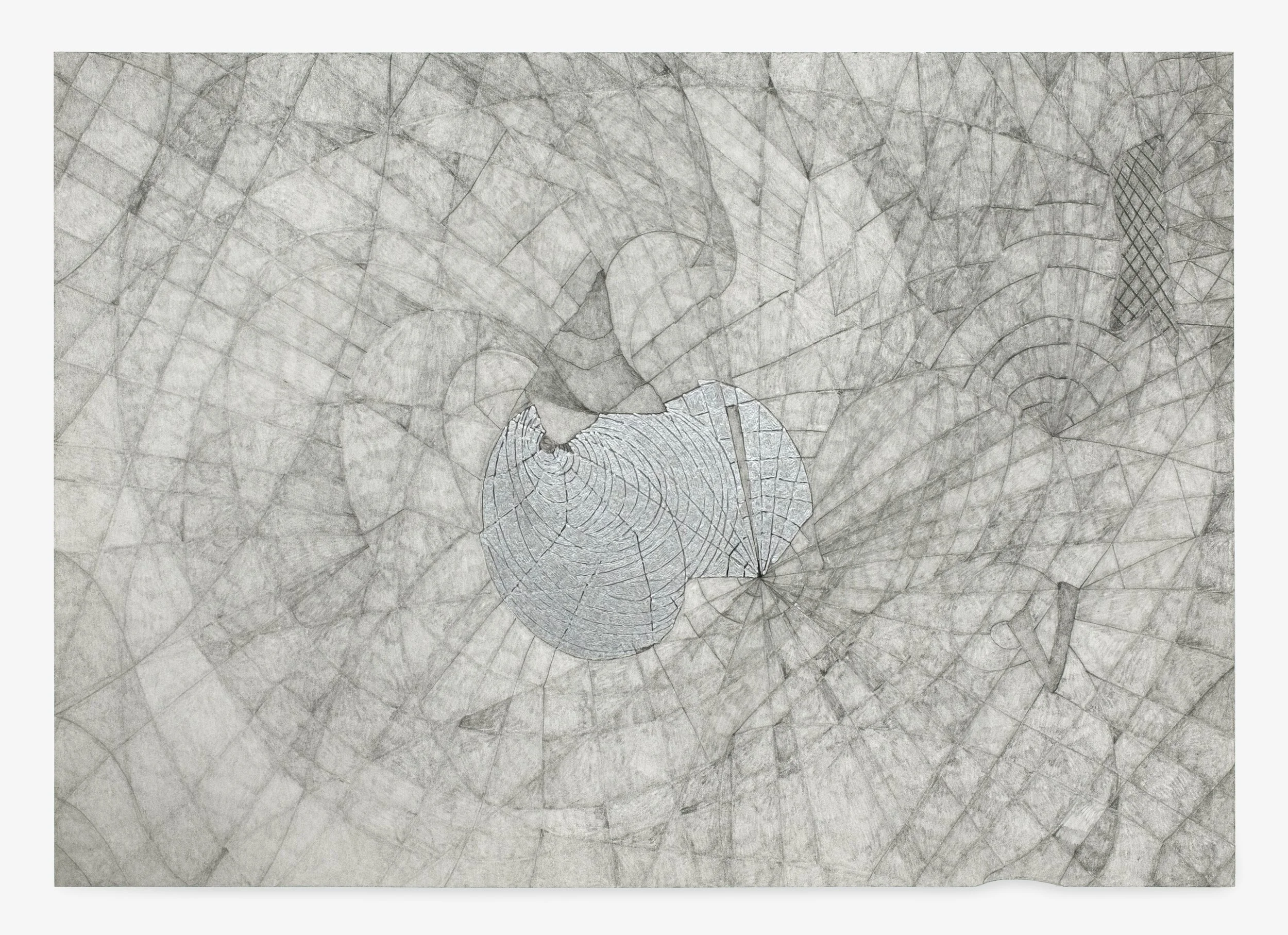

For others, obsessively repeating gestures and markings on paper or canvas yield symbolic forms and images that poetically translate complex emotional and physical states related to trauma, devotion, and healing.

Working non-objectively, solely through intuition and the compulsion to create, provides a unique testament to artistic ingenuity and often highlights remarkable displays of radical innovation.